Eduardo Gudynas, CLAES

La pérdida de bosques sigue siendo uno de los mayores problemas ambientales en América del Sur. Los datos más recientes muestran que, lejos de detenerse, la deforestación tropical sigue su marcha y aumentó en la Amazonia.

Los nuevos registros de pérdida de bosques en la Amazonia llamada “legal” en Brasil, indican un nuevo aumento. En el período de agosto de 2015 a julio de 2016 volvió a subir, alcanzando los 798 900 has. El año anterior la cifra era de 620 mil has. Esto representa un aumento de 71 % en comparación al 2004, según el Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Especiales (INPE). La mayor pérdida de bosques ocurrió en el estado de Amazonas (54 % del total), seguido por Acre 47% y Pará 41%.

Aunque las actuales cifras están muy por debajo de los picos de deforestación de 2003-4 en la amazonia brasileña, el problema es que se acumula lo perdido este año con lo deforestado en años anteriores.

En Brasil, como en los demás países, la expansión de la agricultura intensiva es una de las principales causas de deforestación. Por ejemplo, el programa Mighty Earth ha analizado la situación en ese país, encontrando que en las zonas de las sabanas arboladas donde opera la megacorporación de agroalimentos Cargill, se perdieron alrededor de 130 mil has de bosques entre 2011 y 2015. Mighty Earth también halló que en zonas donde actúa Bunge, otro gigante agrícola, se perdieron más de 567 mil has en ese mismo periodo.

Si bien en los países vecinos los indicadores son menos detallados, toda la información disponible apunta en el mismo sentido de una grave pérdida de bosques nativos. En Bolivia, se estima una pérdida de 350 mil has, en promedio, cada año desde 2011, según el Centro de Documentación e Información Bolivia (CEDIB). Esa cifra ha aumentado desde las 148 mil has deforestadas anualmente en los años noventa y las 270 mil has registradas en promedio durante la década del 2000.

En Perú, un relevamiento reciente muestras que se han perdido 1800 000 has de bosques amazónicos entre el 2001 y el 2015. Dicho de otro modo, casi dos millones de hectáreas en un lapso de 15 años. Los picos de deforestación tuvieron lugar en el 2005, el 2009 y el 2014.

En datos provistos por el Proyecto de Monitoreo de la Amazonía Andina (MAAP), se indica que las principales causas de la pérdida de bosques son la tala, el avance de la agricultura de pequeña y mediana escala, pero también la de gran escala, la reconversión a tierras de pasturas para la ganadería, la minería ilegal, los cultivos de coca, y las obras de infraestructura, como las carreteras.

Las zonas más afectadas en Perú están en la Amazonia, en las regiones de Huánuco y Ucayali, pero también existen otros sitios degradados en los departamentos de Madre de Dios y San Martín.

En Colombia, los datos más recientes muestran una pérdida de más de 120 mil has de bosques en 2015. Esa superficie deforestada es menor a la del año anterior (más de 140 mil has en 2014), pero de todos modos muestra que el proceso continúa. Según el Ideam, para el año 2015, el 60 % de la deforestación nacional se concentra en cinco departamentos: Caquetá, Antioquia, Meta, Guaviare y Putumayo.

En Argentina continúa el problema de la deforestación, con el agravamiento que un tercio ocurre dentro de áreas protegidas, las que supuestamente servirían para proteger los bosques. Según Greenpeace, el 80% de la pérdida de bosques ocurre en Santiago del Estero, Formosa y Chaco, en el norte del país.

Por lo tanto, la tendencia que se observa es que las mayores selvas, como la Amazónica, así como otros bosques tropicales y subtropicales, como el Cerrado o el Chaco, están gravemente amenazados. Cada año se pierden seguramente más de un millón de hectáreas de bosques en esos países, y con ello toda la biodiversidad que albergan, desde otras plantas a una enorme variedad de animales. Esto impone severos impactos ecológicos para miles de especies de insectos, aves, mamíferos, etc. La deforestación de cada año se suma a las de los años anteriores, ya que los planes de restauración y reforestación son débiles y limitados, y a que los tiempos de recuperación de un bosque son muy largos.

For the full article click here.

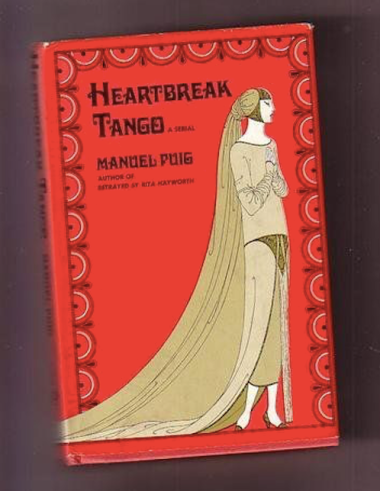

Heartbreak, on the other side, reflects the novel’s theme: the impossibility of long lasting love for all the characters. Nené, Juan Carlos’ official girlfriend, ends up getting married with a man she does not love. Nené’s friend, Mabel, who had maintained a secret affair also with Juan Carlos, gets conveniently married with a man she is not interested in at all, but who provides for her. Raba, a school friend of Nené and Mabel, who is in a lower class position, gets pregnant by a man who rejects her love. The entire microcosm of a small town of the Buenos Aires Province is reconstructed through these life stories. The social importance of marriage, the value given to chastity and virginity, the jealousy, class differences, and gossip are all dramatically depicted in the novel. To some extent, Puig’s novel could be understood as a critique of the morality of 30’s and 40’s Argentina, in which hypocrisy and conservative values were inevitably imposed onto women, especially in small villages distant from, perhaps, more progressive urban centres. However, this critique remains respectful of the thoughts, feelings and emotions of the female characters who, rather than rebelling against the status quo, reproduce it and help perpetuate it.

Heartbreak, on the other side, reflects the novel’s theme: the impossibility of long lasting love for all the characters. Nené, Juan Carlos’ official girlfriend, ends up getting married with a man she does not love. Nené’s friend, Mabel, who had maintained a secret affair also with Juan Carlos, gets conveniently married with a man she is not interested in at all, but who provides for her. Raba, a school friend of Nené and Mabel, who is in a lower class position, gets pregnant by a man who rejects her love. The entire microcosm of a small town of the Buenos Aires Province is reconstructed through these life stories. The social importance of marriage, the value given to chastity and virginity, the jealousy, class differences, and gossip are all dramatically depicted in the novel. To some extent, Puig’s novel could be understood as a critique of the morality of 30’s and 40’s Argentina, in which hypocrisy and conservative values were inevitably imposed onto women, especially in small villages distant from, perhaps, more progressive urban centres. However, this critique remains respectful of the thoughts, feelings and emotions of the female characters who, rather than rebelling against the status quo, reproduce it and help perpetuate it.