Alison Ribeiro de Menezes, University of Warwick

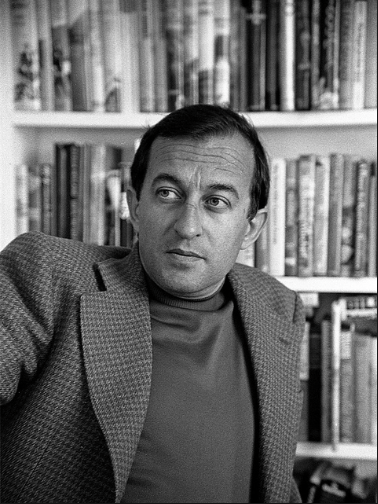

I emerge from the Métro at Bonne Nouvelle and head up the Boulevard Poissonnière towards the Le Gran Rex, feeling as if I have suddenly been transported right into the pages of Paisajes después de la batalla. An eager 26 year old about to finish my doctorate on Juan Goytisolo, I’m on my way to interview the writer I’ve spent the last three and a half years reading and thinking about. What strikes me, though, is that for an author best known for having thrown off the shackles of social realism in the 1960s, in favour of a heavily introverted and metafictional style, the urban fabric that I’ve read about in Paisajes springs up magically before my eyes.

Two decades on, it seems clear that Goytisolo’s writing is more strongly marked by a sense of place than perhaps the postmodernist readings of the 1980s and 1990s were willing to admit. And not just urban places such as the Sentier in Paris, which Goytisolo imagined plastered with graffiti in Arabic in Paisajes, or Tangiers, the subversive protagonist whose streets featured in the magnificent Don Julián, and Djemaa el-Fnaa in Marrakesh, the heart of Makbara. A sense of place, of entangled identities, and of the problems of fighting over these also pervades Goytisolo’s wonderful dispatches from Sarajevo, Chechnya, Palestine.

Goytisolo is of course best known for his cultural subversion of the Spanish literary tradition, and for making his sexuality a defiant rebellion against all normativity. But one of his most interesting pieces is perhaps one of his least read: ‘In memorium F.F.B’, a mock obituary on the occasion of the death of dictator Francisco Franco which can be found in Libertad, libertad, libertad. I always use this short piece when teaching students about the Franco Regime, often in tandem with the opening of Carmen Martín Gaite’s El cuarto de atrás. Both were writers whose lives were dominated by dictatorship, marked by its intellectual poverty, and the struggle of the imagination to open up alternative vistas.

Goytisolo’s In memoriam expressed enormous bitterness towards Franco. My own here expresses admiration for a writer whose best works will stand the test of time. I recently reread Señas de identidad while studying it with my students at Warwick, and I was struck by how relevant its warning against propaganda and fake history still is.

Goytisolo’s in memoriam expressed enormous bitterness towards Franco. My own here expresses admiration for a writer whose best works will stand the test of time. I recently reread Señas de identidad while studying it with my students at Warwick, and I was struck by how relevant its warning against propaganda and fake history still is. The great Spanish novelists of the 60s and 70s seem to have fallen out of fashion, yet their message about deconstructing false narratives and exposing the fallacies of received opinion has never been more necessary.